Patent protection for software inventions in Europe

Computer-implemented inventions can be found in all fields of technologies, ranging from computer and mobile to biotechnology applications.

Article 52 of the European Patent Convention (EPC) states that a patent should be granted in any field, although the EPC also explicitly regards computer programs as not being inventions if claimed as such. Moreover, methods for performing mental acts, playing games, doing business and presenting information are also not considered to be inventions under the EPC.

However, exclusion from patentability under Article 52 of the EPC can be easily avoided. For instance, a claim directed to a computer program will not be excluded under Article 52 of the EPC if it contains at least one feature that is considered to have technical character. In this way, it is sufficient that a claim is directed to a device or to a method implemented in a computer to avoid this. Avoiding exclusion under Article 52 of the EPC is known as the first hurdle and can be easily overcome.

Unfortunately, after overcoming the first hurdle, all the non-technical features of such a claim will be ignored when undergoing the assessment of inventiveness step. This is the second hurdle and usually cannot be overcome as easily as the first.

The EPC does not provide a definition of what is technical, but relevant case law of the European Patent Office boards of appeal provides some indications.

What is technical?

Inventions related to user interfaces, business methods, mathematical methods and simulations require extra care in Europe. Inventions related to image processing and cryptography are usually considered to have technical character in Europe.

One way of arguing that features of a user interface are technical would be, for example, claiming that the feature provides some kind of positive effect on the resources of the device, such as, for instance, reducing memory use or processing time, optimising the use of the display area or providing higher security. This also applies to business methods. If the system involves some kind of communication between devices, bandwidth would be considered a resource and a possible argument supporting that a feature is technical would be that it reduces bandwidth use.

Considerations for user interfaces

Inventions related to user interfaces risk being excluded from patentability through being considered mere presentations of information. According to well-established case law, presentation of information covers both the cognitive content of the information presented and the manner of its presentation. This is not limited to only visual information, but also includes other presentation modalities, such as audio or haptic. On the other hand, data encoding schemes, data structures and electronic communication protocols representing functional data are usually not regarded as presentations of information.

The context of the invention, the task the user carries out and the actual purpose are taken into account when assessing the technicality of a user interface. If the invention credibly assists a user in performing a technical task through continued and guided human–machine interaction, it will usually be considered technical. However, an alleged effect of an invention cannot depend on the subjective interests or preferences of the user. In this way, displaying data in a colour-coded way instead of using numerical values is usually considered a subjective user preference and therefore non-technical, while presenting the internal state of a technical system that enables the user to properly operate this technical system, or displaying several images side by side in a low resolution and allowing selection and display of an image at a higher resolution, are usually considered technical.

Considerations for mathematical methods

Computational models and algorithms, such as those for artificial intelligence, blockchain and simulations, are per se of an abstract mathematical nature. Mathematical methods are specifically not regarded as inventions under the EPC. Therefore, inventions closely related to mathematical methods must provide a technical effect serving a technical purpose. This can be the case if the invention is directed to specific application in a field of technology or is adapted to specific technical implementation. EPO guidelines provide multiple examples of possible technical contributions of mathematical methods. For instance, controlling a technical system or process, such as an X-ray apparatus or a steel-cooling process, is usually regarded as being technical. In a similar way, optimising the load distribution in a computer network is also considered technical.

Decision G1/19

Decision G1/19 was taken by the EPO’s Enlarged Board of Appeals (EBOA), and deals with a European patent application concerning a computer-implemented method, program and apparatus for simulating the movement of a pedestrian crowd through an environment to aid the design process of a building.

In this decision, the EBOA made it clear that the assessment of whether a feature contributes to the technical character of the invention for computer-implemented simulations should be no different than for other computer-implemented inventions. The EBOA also found that the long-standing COMVIK approach is suitable for the assessment of inventiveness step of computer-implemented simulations. According to this decision, computer-implemented simulations should not be treated differently to other computer-implemented inventions.

Moreover, in this decision, the EBOA considered that requiring a direct link with (external) physical reality for computer-implemented simulations is not necessary. Technical contribution could be established, for instance, by features within the used computer system. There are also many examples in which the potential to produce a technical effect (which may be distinguished from direct technical effects on physical reality) has been taken into account when assessing the technicality of an invention. Potential technical effects could be considered when data resulting from a claimed process is specifically adapted for a technical use or if the technical use of the data is implied and extends across the whole scope of the claim. However, this would not be the case if the scope of the claim also covers other uses that are considered non-technical. In such a case, the claim would not be inventive over its whole scope.

The EBOA also addressed the relevance of the technical nature of the simulated system or process, concluding that some simulations of technical systems do not contribute to inventiveness, while it is possible that simulations of non-technical systems do contribute to inventiveness. What should be taken into account is whether the simulation contributes to the solution of a technical problem. To answer this question, the same criteria apply as for other computer-implemented inventions.

The EBOA made clear that the assessment of whether a feature contributes to the technical character of the invention for computer-implemented simulations should be no different than for other computer-implemented inventions and that the long-standing two-hurdle approach is suitable for the assessment of inventiveness step for computer-implemented simulations.

If a computer-implemented simulation has no impact on the internal functioning of the computer, most of the time, it will be quite challenging to limit the claim to any specific technical purpose without incorporating a direct link with physical reality. Thus, after a very long procedure, not too much seems to have changed in the way computer-implemented simulations should be treated.

In sum, Decision G1/19 established that:

- a direct link to reality is not required;

- a potential technical effect is sufficient (eg, output data specifically adapted for technical use); and

- the technical use of the data may be explicit or implied, but must extend across the whole scope of the claim.

Strategies for protecting computer-implemented inventions

What to do

You should either file a patent application, keep the invention a secret or publish the invention.

There are several strategies to consider when thinking about protecting computer-implemented inventions. The most straightforward one is to file a patent application. However, keeping the invention a secret might be a better option if, for instance, the patent case law is not favourable in terms of patent eligibility or it is hard to detect that a competitor is infringing your patent. This option entails some risks because the invention might be made public if, for instance, an employee with the required knowledge leaves to join another company. Another drawback of keeping your invention secret is that a competitor might arrive at the same invention and file a patent. In this case, you might be blocked from using your own technology. Thus, a third option would be to publish it to avoid competitors protecting an identical invention.

Where to protect

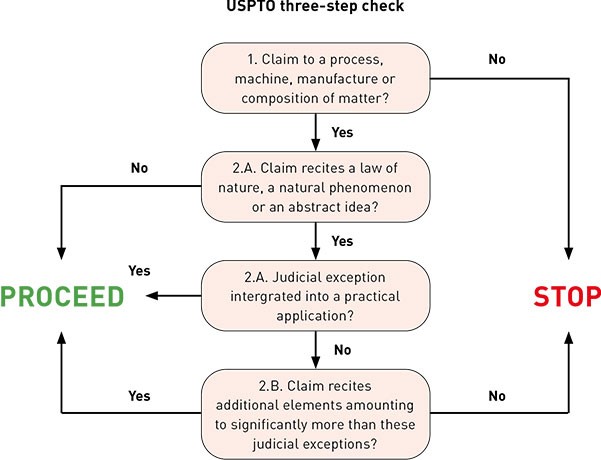

When deciding where to protect your artificial intelligence software, there are several issues to consider, such as where your market and competitors are. For computer-implemented inventions, it is also important to consider that different jurisdictions have different approaches to this kind of invention. As an example, the Chinese, South Korean or US patent offices will treat computer-implemented inventions in a different way to the EPO. Specifically, the United States Patent and Trademark Office applies a three-step check instead of the two-hurdle approach practiced by the EPO.

This approach assesses, in its first step, whether the claim is directed to an allowable category, namely a process, machine, method of manufacture or composition of matter. If the claim is not directed to one of these categories, then it relates to an ineligible subject matter and will be rejected. Otherwise, the approach continues to check whether the claim recites one of the judicial exceptions: a law of nature, a natural phenomenon or an abstract idea. If the answer is no, then the claim is of an eligible subject matter. If the claim does recite a judicial exception but said judicial exception is integrated into a practical application, the claim is also considered to be of an eligible subject matter.

If the exception is not integrated into a practical application, the claim is considered to be directed to the exception and further analysis is performed in the final step. This final step evaluates whether the claim recites additional elements that amount to an inventive concept (significantly more) than the recited judicial exception. If the claim as a whole amounts to significantly more than the exception itself (ie, there is an inventive concept in the claim), the claim is eligible, while if the claim as a whole does not amount to significantly more (ie, there is no inventive concept in the claim), the claim is ineligible.

On its website, the USPTO provides examiner’s guidelines to apply this three-step check. The guidelines contain multiple useful examples that illustrate how each of these steps might be evaluated by an examiner.

Conclusion

Inventions related to user interfaces, business methods and mathematical methods require specific, extra care. Different strategic options should be considered as filing a patent application might not be the best approach. The differences between jurisdictions when dealing with computer-implemented inventions should also be considered.

Applications related to computer-implemented inventions should be carefully drafted, taking into account the particularity of this kind of invention. The patent application should contain as many technical details and effects as possible. This improves chances of successfully arguing later that certain features are technical. For this, it is important to ask the technical implementers which technical difficulties they encountered and how they solved them. Features should provide objective technical effects that do not depend on the wishes or preferences of the user.

In Europe, it is important to incorporate as many features as possible related to how the devices perform the actions – for example, in terms of energy savings, time reductions, more efficient operations or higher accuracy compared to existing methods.

Credits

This article first appeared in IAM Innovation & Invention Yearbook 2023, a supplement to IAM, published by Globe Business Media Group - IP Division. To view the guide in full, please to the IAM website.

IAM Innovation yearbook 2023